-

Posts

2,432 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

182

Monarcheon last won the day on January 8

Monarcheon had the most liked content!

About Monarcheon

Profile Information

-

Gender

Female

-

Location

USA

-

Interests

Cooking, Music, Drama

-

Favorite Composers

Gershwin, Ravel, Webern, Shostakovich

-

My Compositional Styles

Maximalist, Modern-Classical, Musical Theatre

-

Notation Software/Sequencers

Finale 25, Logic Pro X

-

Instruments Played

Cello, Guitar (classical), Piano, Violin, Percussion, Conductor

Recent Profile Visitors

Monarcheon's Achievements

-

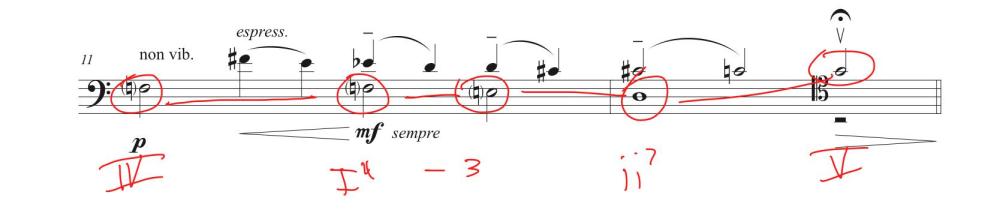

Anything I say isn't gonna be very useful, since you've clearly gotten a performance of it, so it's obviously “good enough,” but I'll throw some stuff out. What an interesting piece, here. It has some very Barber cello concerto-esque vibes, mixed with almost a little bit of Meyer's violin concerto? I love the harmonic language you used throughout and it's very refreshing to see some good string writing. I really liked the transition back to the opening material: I love cascade effects because I'm a normie, but it's used really well here to bring us back to the original register too, which is clever. I think the only real musical note I have is just wanting to hear a little more textural variation. Like, I think the upper strings are homophonic with each other essentially the whole time, which is admittedly a nice split from the full homophony of the intro/ending material, but it feels like—especially at big moments—there could have been some more counterpoint. I have a few score nitpicks, like sometimes your markings that feel like they should apply to the whole group aren't done so (e.g., cresc. in bass in m. 16, mp for cello in m. 17). Bass note spacing issue in m. 73, etc. I was very surprised to see you mix flats and sharps in m. 77, especially when the cello acquiesces to the B major in the orchestra by the end of the measure, but I understand wanting to make the contour clearer in the solo instrument. Have you considered using beam over rests? I'm sure you have; it's just some of the rhythms starting in m. 58 are (despite being totally fine with practice) kinda rough to look at on first glance, and you're at the disadvantage of doing it with 16ths and not 8ths as is normal for that kind of texture. m. 62, in my mind, clef changes are applied only to the note and not any rests; I'm sure it makes spacing look better having the clef change in the solo be just at the beginning but it made me do a double take. And I'm just selfish, but I'd have loved to see some bowings (🙂), just for that little extra professionalism pop, haha. Great work and very enjoyable to listen to!!

-

Poll concerning AI sub-forum

Monarcheon replied to PeterthePapercomPoser's topic in Announcements and Technical Problems

Although I hold that AI music is still technically music, however unethically created it is, AI music is certainly not composed. It's more so generated, and this site is arguably about the composition of music, not the music itself (although, it seems that many users haven't grasped this). For that reason, my mind is most open to being changed on Question 2. Currently, I've selected the second option—creating a sub-forum and barring AI submissions to be entered into competitions—but if someone was to push hard for banning all AI music on account of it being against the spirit of being a composer, then it's not like I'm gonna push back too hard. However, I'm sympathetic to the idea that AI is here and will be here for a while, if not permanently, so banning it outright feels a little close-minded when there's still things to be learned from it (more socially and economically than practically), just not strictly composition. I'm seeing a lot of exceptions being made for vocals/SFX creation after something has been written and making rules that are clear and foolproof to distinguish that is going to be hell, but I think it's better to have the word of another person as to the extent AI was used rather than just trying to use an AI checker or a filter. As pointed out before, those things are really murky and spotty. I don't really care about the “emotions” behind it, because—let's be real—tons of music gets written for a paycheck with no emotion or humanity. That's not a measurable quality, as far as I'm concerned. I also don't really care about the amount of effort or time put into a piece; some things are just easier for different people. As for feedback, have you seen Google AI? It could tell me the sky is blue and I'd look out my window to go check. No way in hell is that level of intelligence going to have reasonable critiques beyond just telling me what Roman numerals are being used, which isn't analysis in the first place. -

fantasia on jingle bells (2025 Christmas Music Event Submission)

Monarcheon replied to Monarcheon's topic in Chamber Music

@chopin Glad you liked it! Yeah, the whispers of the old theme coming back was a really captivating idea for me, but the best part is that I'm sure another talented analyst could analyze it in a completely different way than I did! @Luis Hernández Thank you! @Thatguy v2.0 Nonsense, the fact that you're able to even listen to it—let alone enjoy it—means that you're worth your salt! And yes, it's why I have so much solo cello rep... I can actually play it. 🙂 @Wieland Handke Thank you so much, that's a great image! And wonderfully wholesome for something that be construed as being so eerie. My respects and humble thanks to all of you! -

I'm beginning to write a small oratorio

Monarcheon replied to Cafebabe's topic in Orchestral and Large Ensemble

Hey, this is great and has a lot of potential; I hope you keep writing! Lots of very cool moments and bits like the way you harmonize the very first “Shew me thy ways, O Lord”; vii˚7/vi–vi? How cool is that, especially since it's a lot more harmonically standard the second time around. I'll mainly focus here on “Shew me...” since it's a little easier to parse the score quickly: 1. m. 5's two-beat long semitonal dissonance is already striking enough, but having the suspension resolve upwards is even more noticeable. Not a strict problem, per se; it's just maybe a little overly noticeable. 2. m. 7, V7 without the third except in an ornamental figure, approached by 4-5 motion in first species. 3. mm. 8–9, “Shew“ is three quarter notes for a one-syllable word. There's a couple other measures where you have one syllable sung on repeated notes. 4. m. 11, unnecessary whole rest break in V1. 5. mm. 14, 17 & 22, similar issue to Point 2. Also, unnecessary breaking of the quarter rest in vocalist's part in m. 14. 6. m. 26, “O Lord” breaks the more natural setting of the scansion you had in mm. 10–11. 7. Keep “teach” as one word spelled correctly (don't double the “e”). 8. I would add some bowings; some are great, like the one you have in m. 13 in V2, but take a little time to make sure that the most natural style (down bow at the beginning of the measure, especially with all of these quarter notes) is preserved unless marked otherwise. Of course, Points 2 and 4 can be fixed with a continuo part with figures; I heard it in the background, but it just seemed to double the celli and bassi. Again, it's exciting to see where this could go! Solid start! -

fantasia on jingle bells (2025 Christmas Music Event Submission)

Monarcheon replied to Monarcheon's topic in Chamber Music

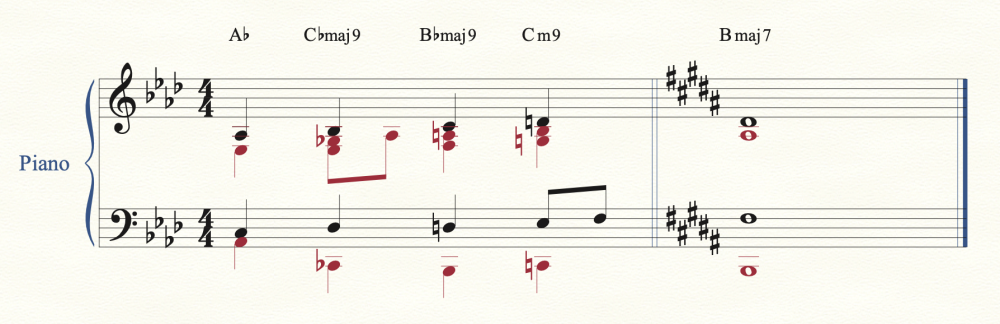

Hi @PeterthePapercomPoser, thanks for the kind words. Yes, a lot connects to the original them in some way, but obviously in a way that's idiosyncratic to me, right? There are some very obvious things like this... ...and there are other pretty obvious quotes: mm. 17–18 are just the latter half of the main theme's antecedent phrase, mm. 19–20 are a condensed version of the antecedent as a whole (<E, G, C, D, E, F, (E,) D, G>), and the notes for the tremolo parts are the first three notes of the theme (<E, G, C>). But then there are just decisions that I made artistically. For instance, I think the idea that the main melody of the non-introductory carol can be condensed into a pentachordal diatonic subset with only one semitone is very fascinating, so I emphasized the semitone throughout my setting as like an opposite to diatonicity. So lots of semitonal dyads (both harmonic and melodic) all about. Sounds rough, which I like, and also meets the design philosophy. For example, passages like m. 16 where there are both ic1s and ic2s, which, to me, emphases that friction between the diatonic and chromatic. But, to be honest, I didn't think that hard about it, haha. Most of the time, I just kinda liked the dissonance 🙂 I think the fact that you can hear echoes of the original is way more interesting than having every single thing be attached to it. Thanks again for your eyes and ears! -

Lovely little piece. I guess I shouldn't be surprised that a chain of secondary dominants works so well as a fugue subject, but I think you bring out its fullest potential. It makes little moments like mm. 32–33 so lovely because it's so diatonic but keeps the spirit of the sequence. Really cool to see what parts of the theme you kept and selected in certain parts. I think m. 37 is the only bar that I'm not as big a fan of: the P5 (vaguely on ii?) into A4 (vii˚) feels a just the tiniest bit awkward because (I think? I've been having a hard time trying to think of a reason...) the third is neglected twice.

-

2025 Christmas Music Event!

Monarcheon replied to PeterthePapercomPoser's topic in Monthly Competitions

My submission for the event can be found here: -

Hello, all. Coming at you with something a little different for the event, but I hope you find it at least interesting, even if you don't particularly like it. I've basically decided to get really good at writing for strings nowadays, and since I'm mostly an atonalist, cello is the easiest since computers can't play that kind of stuff; the implied timbres are super important. So enjoy hearing me poorly play this miniature fantasia on Jingle Bells. I promise there's a method to the madness 😄

-

2025 Christmas Music Event!

Monarcheon replied to PeterthePapercomPoser's topic in Monthly Competitions

I'm game. Vamos a ver que podemos hacer. -

Key Change

Monarcheon replied to BlackkBeethoven's topic in Incomplete Works; Writer's Block and Suggestions

I'm more of a voice-leading kinda gal, but I came up with this on the fly. I have no idea if it works in the context of your own work, but in general, I'd advise starting with moving lines that mesh well, then filling in gaps. Happy accidents happen all the time! -

Calling Oboists! Need a little guidance

Monarcheon replied to J. Lee Graham's topic in Composers' Headquarters

@PeterthePapercomPoser Hmm, I'm not exactly sure what you mean; I don't see anything missing on my end. I didn't replace the file with anything, just changed my explanation! -

Calling Oboists! Need a little guidance

Monarcheon replied to J. Lee Graham's topic in Composers' Headquarters

@PeterthePapercomPoser Oopsie, yep, fixed. (Unless it was a bass oboe 😮) -

Calling Oboists! Need a little guidance

Monarcheon replied to J. Lee Graham's topic in Composers' Headquarters

Huge disclaimer: I am not an oboist. But I'd imagine it really depends on what you need the oboe to do. My first immediate thoughts go to the intro in Haydn's oboe concerto which, if I remember correctly, holds onto C6 for quite a while. It does go up to D at the end of the first movement, but only on a non-diatonic chord, so that extra brightness is warranted. Even then, it's really short. I compare that to his contemporaries' concerti, Mozart's, Kozeluch's, and Ferlendis's. On a quick scan, I don't much see anything past C in any of them, though I see some similarities to Haydn's: Kozeluch is also comfortable holding onto C5 for a while and Mozart uses D5 as a brief note in a higher moment. From what I remember for Ferlendis's, it plays it pretty safe, all things considered. I don't have the music, but a quick Google search shows that nothing over C5 is really lingered on. For that reason, my gut tells me to say that C5 is where you edge out for longer, full-bodied sounds and things above it like D5, etc., can be used quickly on occasion, but not in the same way as C5, and certainly not commonly. But that's all conjecture; I don't actually know the ins and outs. Luckily I write modern music, so those suckers have to deal with whatever I give them, hee hee hee! -

I've always prioritized voice leading in my chord construction; sometimes, I just slap a root on there and it works out! Thank you both for listening!

-

I wrote some variations on Dies Irae for string quartet

Monarcheon replied to 林家興's topic in Chamber Music

As a cellist, I personally like seeing the downwards arpeggio line, but I suspect Scriabin wrote it the way he did because he wanted to specify that the root(?) occurred on the beat. I see both having merit in different cases, but—generally—the arp. line is probably fine.

.thumb.png.8b5b433a341551e913a34392660bc95b.png)

.thumb.png.1e2763f479362bbb522da50d31ef2e50.png)