Search the Community

Showing results for tags 'masterclass'.

-

Please respond here if you want to see certain things covered in one of the future masterclasses!

-

High school and two-year college composers are invited to submit scores for performance at a composition festival, New Music on the Bluff 21, at Loyola Marymount University (the festival will be online in 2021). The eight selected finalists will receive performances of their pieces on April 17th, 2021, will meet on Zoom with a faculty composer for an individual private lesson, and will participate in master classes with festival faculty. Works can be scored for violin and piano, a selection of solo instruments, or can be fixed media electroacoustic or electronic pieces in any style. Application is free and all eligible applicants will be invited to the master classes. The application deadline is January 31st, 2021. View the call for scores here: https://cfa.lmu.edu/programs/music/beyondtheclassroom/concertseries/newmusicontheblufffestival/

-

- festival

- call for scores

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hello composers! This will be the place where I will share one classical composition including saxophones per week. The videos are not mine! As a saxophonist, I notice that still many composers do not use the saxophone in classical music. The most important reason for this is because they do not know how to apply the instrument. I often get the question if I could give some study advices for saxophone writing. My answer is always that one has to listen and study the works of our predecessors. This topic is meant to inspire and stimulate composers to write more music for the saxophones. Contents Graham Lynch - Unreal Promenade for Saxophone Ensemble (2015). Jean Françaix - Cinq Danses Exotiques for Alto Saxophone and Piano (1961). Georges Bizet - Suite No.1 from the drama l'Arlésienne (1872). Claude Debussy - Rhapsodie for Saxophone and Orchestra (1901 - 1911). Slava Kazykin - ''Bachiazzola'' for Saxophone Quartet (n.d.). Mark Watters - Rhapsody for Baritone Saxophone and Wind Orchestra (2001). Iannis Xenakis - XAS (1987). Mozart / Arr. Niels Bijl - String Quartet No.15 in D minor, Kv. 421a. Paul Creston - Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano, Op.19 (1939). Erwin Schulhoff - Hot Sonata (1930). Carter Pann - The Mechanics for Saxophone Quartet (2013). #1 Graham Lynch - Unreal Promenade for Saxophone Ensemble (2015). More information in the description of the video. Best wishes, Maarten Bauer

- 38 replies

-

- masterclass

- bauer

-

(and 5 more)

Tagged with:

-

Instructor: @Monarcheon Writing Requirement: Soundwalk Special Requirement: Compose a general soundwalk A soundwalk is a composition intended to guide a reader along the path you prescribe. These compositions last generally last around 30 minutes to an hour and are intended to be the most sonically engaging possible. Soundwalks are composed as lists of instructions to guide the listener on their journey. Normally, soundwalks are composed with specific locations in mind, but it is more fulfilling and viable to compose general soundwalks, where the instructions should be able to be applied in most places. For example, a normal soundwalk I would compose would have the city I live in, Seattle, in mind while I write instructions, and would mention specific places, like the University campus, or the light rail stations. A general soundwalk would be more likely to include compass directions, indoor vs. outdoor specifications, and times. Here is an abridged example of a normal soundwalk, with the University of Washington in mind: Striking Sounds about the Stevens Loop by Alex Sanchez Remarks: This soundwalk calls for the traversal of stairs. If this is not possible for you, simply enter the stairwell, participate in or simulate some of the activities suggested, then take the elevator to the destination floor, if necessary. “Striking” is both a verb and an adjective; we will treat it both ways. At various points during the soundwalk, you will be asked to strike objects. Also, you will be asked to reflect upon or simulate the sounds you create--and stumble upon--during your walk within the various ambient and sonic environments you encounter. Materials: Carry various objects made of various materials with which to strike other objects found during the walk. Also, if possible, leave behind any delicate electronics so that your backpack becomes a “striking-sack” with which to create “booms” in reverberant stairwells. Your hands are also valuable striking tools! Also, it is recommended to wear socks and (fully to semi-)waterproof, but absorbent shoes. Instructions: For best results, this soundwalk should occur during a dry, somewhat windy school day, at or slightly before the main lunch rush. Begin the soundwalk outside Music room 216, our meeting spot for class. Take a minute or two to explore the sounds of the lockers in the hall. Try opening and closing them with varying degrees of force, striking them in various locations with your striking tools, singing into them to find their resonances, etc. What are the “highest” and “lowest” sounds you can make? Which sound is the most striking to you? Which aspects of that sound are distinctive and make that sound striking? Remember your favorite sound; you will attempt to recreate it later. Walk up the stairs, listening to the sound of your footsteps. Try to explore the variety of sounds you can make by stepping lightly, heavily, dragging your feet, etc. Exit through the doors leading to the Drumheller Fountain. Walk there, and take a lap around the fountain. Listen to how the sound of the fountain changes as you walk around it, and also to how the ambient sound around you changes as you move to different areas in the space. Upon completing the lap, walk north towards Red Square and try striking the ground as go to see how the ground reacts to your striking tools. Upon arrival, find pairs of conversations between people in Red Square. Stand exactly between the loudest of them, and face one of the conversations, watching their mouths as speak. As you do this, focus on the sound of the conversation behind you, ignoring the sound of people in front. Do this for 2 more pairs of conversations: one at farther distance, and one at closer distance. How does the experience of listening change at these distances? Walk into Odegaard, noting the change of ambient sound, and up the stairs to the 3rd level quiet work area. Sit there for 3 minutes, reflecting on the sounds you heard so far in the sound walk. Which was your favorite and why? Which details of the sounds can you remember? Which were the most striking and why? Leave Odegaard the way you came in and walk to the sculpture by the Law School we saw in class. Strike it with your striking tools. Try different locations. Does the fundamental pitch of the sound change depending on where you strike it and which striking tool you use? What about the timbre and the resonant overtones? Can you recreate the sounds you made with the lockers here? What about other sounds that were striking to you? Which sound of the sculpture is most striking and why? Walk back to Music 216, and try to recreate your favorite sound on the lockers by any means necessary. If your favorite sound was from the lockers, use your next favorite sound. Here is an example of a general soundwalk, with no specific location in mind: Soundwalk – Polymorphism by Greg Bueno Triangulate. If you are indoors, exit. If you are outdoors, remain so. Choose west, but go south. Walk till you find a spot where the trees do not obscure the sky. If you must deviate from south to reach this spot, do so. Remember that you have already chosen west. Find a suitable place to sit. Optional: Remain standing. Fix your gaze at a single point. Do not strain your eyes. Begin listening. Count slowly to 23 or until you perceive the passage of one and a half minutes. Do not use a timepiece. Note: You may fall short of that duration. Conversely, you may exceed it if you are distracted by thought. These outcomes are acceptable. You may stop fixing your gaze. Continue to do so if it helps you to listen. Identify the sound that captures your attention the most. You must not refer to this sound by its name. Until instructed to do so, refer to it as POLYMORPHISM. Ignore POLYMORPHISM but keep it in your heart. Resume listening. As you continue to listen, take your pulse. Suggestion: You may find your pulse easier on your neck than on your wrist. Do not listen to your pulse. Feel it instead. Count slowly to 17 or until you perceive the passage of one minute and 15 seconds. Do not use a timepiece. Reject POLYMORPHISM. Optional: Regret the act of rejection. You may stop taking your pulse. Continue to do so if it enhances your experience of listening. Resume listening. Concentrate on a steady sound. Note your reaction to that steady sound. Remember a time you should have felt sad but did not. Concentrate on the steady sound again. Note whether the memory of the previous step affected your perception of the sound. Resume listening for a length of time you perceive to be two minutes. Do not use a timepiece. Acknowledge POLYMORPHISM has forgiven your rejection. Accept it back in your heart. Hum to the pitch of the same steady sound on which you reflected about not feeling sad. Optional: Forgive yourself for not feeling sad. Recall the original name of POLYMORPHISM. Say the original name of POLYMORPHISM to the pitch of the steady sound. Think the word POLYMORPHISM as you say its original name. Stop at a comfortable interval. Resume listening. Go north, but choose east. If you were indoors at the start of the piece, you may return there. Optional: Seek another destination. You have concluded the piece. I would like to see some general soundwalks if you have time to write one, but understand if a normal one is required.

- 2 replies

-

- soundwalk

- composition

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Instructor: @MonarcheonStudents Allowing: 7Initial Writing Requirement: As many bars as it takes to fit at least 7/14 techniques. Solo cello. Initial Writing Requirement Deadline: May 23rd Pretty simple class. Write a piece that incorporates at least 7 of these, but make sure that the cello still plays normal notes too, so that the extended techniques can be jarring and inventive. Also keep in mind that it will occasionally be difficult to switch between techniques very quickly, for example going from 3rd method to scordatura will be difficult to execute in a quick change. Keep this in mind when transitioning between sections. I will personally record all the submissions that best and most logically use the instrument's capabilities within the piece. Instrument Family Technique Name How It's Performed How to Notate String 2nd Method Turn the instrument on the side (for higher strings), bow the side of the bridge (harder for cello, but can do). Write by using an X notehead in the middle line of the staff. Label "2nd". String 3rd Method Bow the string beyond the bridge. Write by using an X on the line where the open string would be. Label "3rd". String Col legno Tap the bow's wood on the strings. Mark normal notes, and mark "col legno". String Tap/Hit Tap on the instrument in a designated location. However you want, but be logical. Be sure to label to tap, and also where to tap/hit. String Vibrato Markings Specfy the vibrato players use. I use (v+), (v-), and (v.) to mark with vib, without vib, and with slow vib, respectively. String Scratch Tone Very harshly bow the string to where the pitch is indeterminate. Use a doubled bow marking (i.e. make a smaller down bow marking within a normal one, same with up.) String Voice/Sing Speak, sing, or whisper instead of play the instrument. Use X noteheads to mark a contour of the line if speaking, normal notes, if sing. Mark lyrics below, and mark for them to sing/speak. String "Death Tones" Play an indeterminately high pitch, sound better when gliss.'d to. Normally harmonic triangles are used. These sound better as tremelos. String Ponticello Bow near the bridge. Pairs well with tremelo. Mark normal notes with "pont." String Silent Fingerings String player plays the left hand without using the bow or pizz. Mark "+" and a line/bracket designating the area of where the technique is to be used. String Scordatura String player will detune their instrument. Can be done within the work too. Use words to label detuning and retuning if in the middle of the piece. Dictate the open strings if at the beginning. MAKE SURE THE TUNING IS NOT FAR AWAY FROM THE NORMAL STRING. String Artificial Harmonic Ground fundamental with lower finger, and harmonic up a fourth. 15ma Normal note to indicate the fundamental. Harmonic notation for the second note, a fourth above. String Snap pizz. Harshly pizz. the note so the string rebounds off fingerboard. Mark a pizz. section with the cello thumb symbol (circle with line coming out of it). String Buzzed pizz. Lightly touch string with fingernail when pizz.'ing. Mark a pizz. section with "buzz", commonly using a line or bracket, designating the section.

- 8 replies

-

- extended techniques

- strings

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

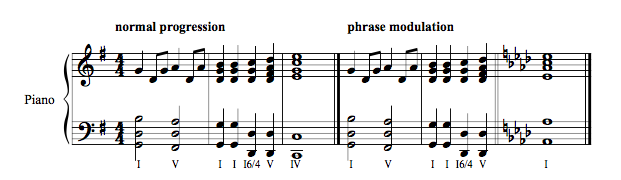

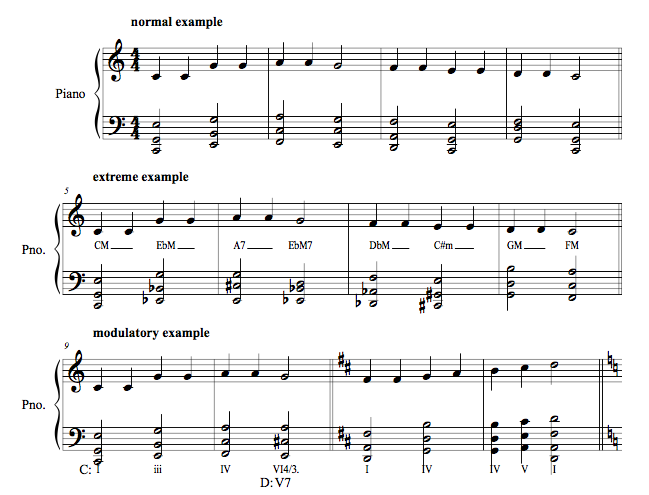

Instructor: @Monarcheon Students Allowing: 7 Initial Writing Requirement: use as many bars necessary, piano Initial Writing Requirement Deadline: April 20th Special Writing Requirement: use and label all 3 techniques In the second of these harmonic technique series, it's going to focus a lot on modulation and phrase alteration. These are good for keeping your audience guessing, and can easily grow and come back from a developing arc, at least harmonically. These are: Saturation (chromatic or diatonic) Direct/phrase modulations Reharmonization Saturation is a way of using all the tones in either a chromatic or diatonic scale before moving on with the phrase. A lot of you might refer to Schoenberg's twelve tone rows, but chromatic saturation has been used a lot before that, in pieces by Hugo Wolf. Mozart even attempted this kind of writing in the fourth movement of Symphony No. 40, KV. 550, in G minor, right before the development starts. Chromatic saturation is simply using all of the notes of the 12 tone spectrum within a segment of music. Here's the Mozart example from before: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B5fqVYXVDwU#t=03m30s It creates a perfect location to start a new phrase in a completely new place (the V/V of the key) from the III. Chromatic saturation doesn't all have to be in a row, though. Connecting strings of chromatic chords can achieve the same goal. Diatonic saturation is the same concept of chromatic saturation, but using a scale (any mode) as the grounds of saturation rather than chromaticism. Especially when combined into chords, this method can sound very cacophonous, but still tonal, as the composer resolves the mass of sound into a new phrase. An example from Rautavaara's "Cauntus Articus" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TO3YRZWLvQo#t=04m12s Direct modulations are basically modulations that don't really seem to fit within any traditional tonal analysis. The most common type of this is in pop, musical theatre, or rock music where the key moves up a whole or half step without warning to give the sense of harboring more energy in the song, especially with a repeated motif. Phrase modulations, can be direct modulation, but simply happen in the middle of a phrase to jar the audience, but still stay fluid throughout, most often by keeping a melody or inner voice in constant motion throughout the phrase. Phrase modulations are especially useful in recapitulations of sonata format, or when a repeated figure in any form of music is getting to be a little bit too much. Executing these may seem counter-intuitive, but it requires you to think outside of the realm of diatonicism in one key. If you compare the key of the phrase you're in and the key of the phrase you want to end in, the composition of phrase modulation is "how am I going to bridge those gaps?". Common ways, as said before, can be: ...keeping the melody/inner voice moving, and using accidentals to reach the new key. Ending a phrase in the original key, and instead of ending the melody where the the audience expects it diatonically, make the last note an accidental in the old key, but perfectly fine in the new key. Reharmonization is simply a way of taking a melody and changing the chords underneath it to make it sound new and different. An easy way to do this is take your melody, and find chords that it also sounds good with; sometimes these will be diatonic, sometimes they won't. Oftentimes, to make the new progression sound smooth, composers employ extended chords to help, having the melody end on 9th's, 11th's, or 13th's, so the bass line can move without sounding too jarring. This technique is also good in recapitulations or repeated figures. Using it can also be a great pivot for a modulation.

- 17 replies

-

- modulation

- masterclass

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Instructor: @Monarcheon Students Allowing: 5 Initial Writing Requirement: 16 - 32 bars, piano or harp Special Requirement: Must include 3 of the 4 harmonic functions below Initial Writing Requirement Deadline: April 8th Masterclass No. 3 will the first in a series of two classes on basic harmonic extensions: *Italian Augmented Sixth Chord *French Augmented Sixth Chord *German Augmented Sixth Chord *Neapolitan Sixth Chords Basic Guidelines: Augmented Sixth chords are used, typically as a way to create maximum harmonic tension before resolving to the dominant. The basic way to structure these are to take the dominant of whatever key you happen to be in, and go one half step up above and below it and place it as an interval. Example: D minor -> Dominant: A -> Go up one half step above/below: B-flat, G-sharp. The "type" of augmented sixth chord that results from this is dependent on what other notes you add. If you add the tonic of the tonic key, it becomes an Italian Augmented 6th chord If you add the tonic of the tonic key and the major supertonic of the tonic key, it becomes a French Augmented 6th Chord (my favorite!) If you add the tonic of the tonic key and the minor mediant of the tonic key, it becomes a German Augmented 6th Chord Examples: D minor -> Dominant: A -> Go up one half step above/below: B-flat, G-sharp [D G# Bb] - Italian [D E G# Bb] - French [D F G# Bb] - German Notice that the German chord, if restacked with the Bb on the bottom will sound like a dominant 7th chord. It is NOT a dominant 7th chord. This is very important when analyzing. Remember these augmented sixth chords mostly always resolve to the dominant. You typically use these chords in minor keys, but this is not always necessary. Neapolitan 6th Chords are based on the tonic of minor key, as a way of creating last minute tension before resolving to the tonic or the dominant. The basic structure of these are to take the minor second of the tonic key and create a major triad. Example: E minor -> Tonic: E -> Half step up: F -> Spell chord: [F A C] In classical harmony, these chords are almost always in the first inversion, because it serves as a predominant (iv chord), where the bass moves stepwise up to the dominant. Another way to extend this is to have the Neapolitan Sixth chord, then go to a tonic chord in the second inversion before moving to the dominant.

-

Masterclass #2: Olivier Messiaen - Compositional Techniques Instructor: @Luis Hernández Instructors should file the following information: Students Allowing: Initial Writing Requirement: Initial Writing Requirement Deadline: Composition Guidelines:

- 21 replies

-

- masterclass

- messiaen

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Instructor: @Monarcheon Students Allowing: 7 Initial Writing Requirement: 32 - 48 bars, cello + piano Initial Writing Requirement Deadline: March 15th Please do not sign up for the masterclass if you know how to write the basics for cello. Here's masterclass No. 1! Monarcheon is a string player herself and can provide lots of good basic instruction for string writing. This masterclass will focus on bowings, pizzicato and left hand position. Please reply in the comments if you'd like to receive catered feedback on these two things. She'll take up to 7 students for this lesson. Once you reply, begin writing under the proposed guidelines and instrumentation and before the prescribed date. Try to follow or include some or all of the guidelines when composing! Also, try to stay within those guidelines and don't try to overextend the purpose of the lesson. Basic Rules: 0. A position on the cello simply means where the left hand is on the fingerboard at any given time. Higher positions are closer to the bridge (the "bottom") and lower positions are closer to the scroll (the "top"). In general, try to stay in the low to middle range. 1. Long crescendos are typically played up bow, in a slur, since gravity plays the peak of the crescendo much better as a down bow. 2a. In standard 2 or 4 bar phrases or rhythmic systems, the beginning of the measure is down bow, and the return at the half bar is up bow. 2b. Down bow is considered the more powerful of the two bows. You can use this to your advantage and have passages with only down bows to really accent a passage. Keep in mind that a lot of down bows in a row in a fast tempo is hard for the performer. 3a. Cellos have the open strings (from lowest to highest), C G D A. This means they are a fifth apart and double stops can be written in a variety of distances from each other with that in mind. Double stops must keep this in mind, and you cannot skip over a string to play a double stop. 3b. Try not to write fifths though, as they are hard to tune. 3c. Thirds are also not always welcome unless they are in a lower position. 3d. Fourths are fine, but remember they will sound awkward due to traditional voice leading rules. 3e. In the lower positions of the cello (closer to the "top") the maximum interval for a double stop is a minor seventh, nearer the high positions, octaves are more acceptable. 3f. Despite being inversions of each other, avoid seconds if possible. Not only are they are to tune, 4. Slurs are NOT expressive or phrase markings. They are bowings. Dynamic markings are your best bet for marking a phrase. 5a. When writing fast passages, try to avoid using a lot of double stops, except when there are a lot of notes in the same position in a row. 5b. When writing fast passages, keep in mind that the positions the player have to traverse should be relatively close or static as you transition. Basically, avoid too much jumping, unless an open string is involved. 6a. Tone becomes a lot less clear the higher you go up on the cello, especially double stops, but also can be strident if you want to have a dramatic peak. 6b. This is especially true for pizzicatos. 7a. Pizzicatos (marked pizz.) follow the same guidelines as double stops in terms of fingering, but are not bound by the curse of having to cross a string. 7b. Fast pizzicatos could not be considered highly. 8. Do not include too many double stops in a row, unless the passage is extremely virtuosic, but we will not really consider that for this lesson. POST COMPOSITIONS IN THE COMMENTS BELOW WHEN FINISHED. DO NOT ADD AN AUDIO FILE.

- 33 replies

-

- lessons

- masterclass

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hi everyone! Welcome to the revamping of the Masterclass forum. Here's everything you need to know: Masterclasses on YoungComposers are like little mini-lessons focusing on a very specific aspect of musical composition. This can be anything from Ear Training to Score Study. Each lesson will be led by a proficient teacher in that field. Instructors will need to know basic composition skills, with an extended knowledge on the topic they will be teaching. As composition topics for these classes are announced, you can respond here in a separate thread if you'd like to be the proctor of the given class. Instructors are expected to make classes engaging, specific, and dynamic. Simply reading a page on orchestration techniques is not very conducive to learning. Participants for these classes are determined by the signup for each given class. When a new thread for that class is opened, the signups will be open. The instructor can decide how many composers he/she/they will be assisting in a given lesson. A good way to engage your students is to have them write a short 32 bar piece with some basic guidelines, then telling them what they missed and what they can improve upon after the fact. Instructors should mainly focus on the area of teaching relevant to the discussion. For now, I will be deciding what classes will be "official". There will be a thread of compositional topics composers on the forum would like to see covered in the future. The time schedule of these classes will be once every 2 - few weeks. Hit "Follow" on this forum to stay up to date on any new topics you might be able to help the community with!~~ I hope you find these helpful!

-

- rules

- masterclass

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with: